STORIES

8372 // BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA

In 1980 the leader of Yugoslavia, Marshal Josip Tito, died, leaving others clinging to ethono-nationalism which rose across Yugoslavia. Upon declaring independence by referendum in 1992 Bosnia and Herzegovina, a Muslim majority, found itself under attack by Serb and Croat forces as Yugoslavia disintegrated along ethic lines. The Bosnian Serb leadership boycotted the referendum to prevent independence, but it was officially declared on 1 March 1992 and Internationally recognised by April 1992. War ensued from 1992 – 1995. The Srebrenica killings were the bloody crescendo of the war which pitted the country’s three main ethnic factions – Serbs, Croats and Bosniaks – against each other after the break-up of Yugoslavia.

In March 1995 Radovan Karidžić, president of the self-declared autonomous Republika Srpska, directed his military forces to “create an unbearable situation of total insecurity with no hope of further survival or life for the inhabitants of Srebrenica.” By May a cordon of Bosnian Serb soldiers had imposed an embargo on food and other supplies that provoked most of the town’s Bosniak fighters to flee the area. In late June, after some skirmishes with the few remaining Bosniak fighters, the Bosnian Serb military command formally ordered the operation, code-named Krivaja 95, that culminated in the massacre.

Potočari, where the Dutch had their peacekeeping base was overrun by Bosnian Muslim refugees after the fall of the Srebrenica enclave in May 1995. The United Nations declared the besieged enclave of Srebrenica a “safe area” under the protection of the UN forces. However, the lightly armed Dutchbat soldiers, were unable to demilitarize the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) within Srebrenica or to force the withdrawal of the VRS surrounding Srebrenica.

On the night of July 11, a column of more than 10,000 Bosniak men and boys set off from Srebrenica through dense forest in an attempt to reach safety. Beginning the following morning, Bosnian Serb officers used UN equipment and made false promises of security to encourage the men to surrender; thousands gave themselves up or were captured, and many were subsequently executed. Other Bosniaks were forced out of Potočari that day through the use of terror, including individual murders and rapes committed by Bosnian Serb forces. The women, children, and elderly were placed aboard buses (some of which had been brought from Serbia) and driven to Bosniak-held territory.

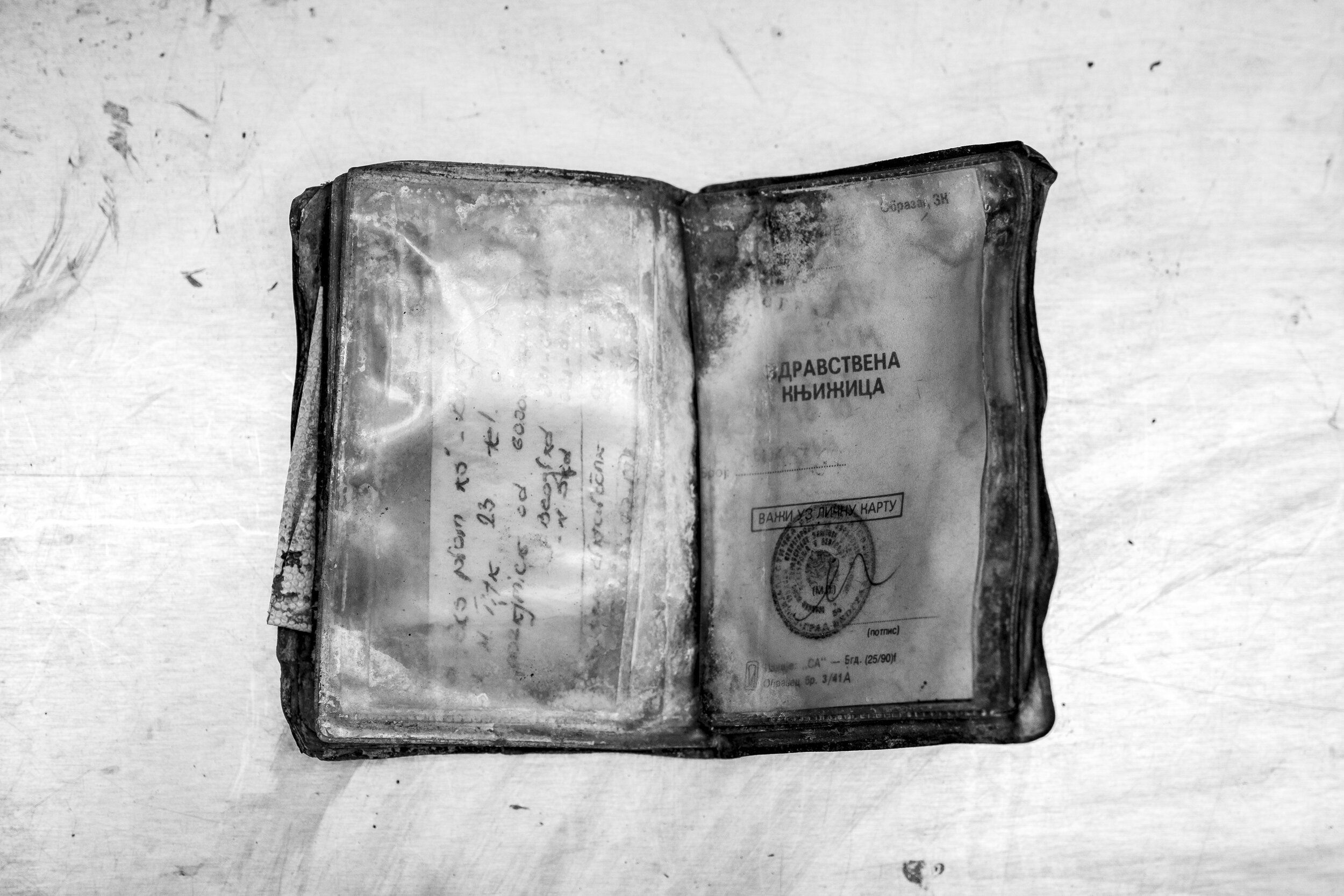

Their bodies were ploughed into hastily dug mass graves and then later excavated with bulldozers and scattered among other secondary and tertiary burial sites to hide evidence of the crimes. The bodies were moved among an estimated 80 mass grave sites.

A list of missing or killed people during the massacre compiled by the Bosnian Federal Commission of Missing Persons contains 8,372names. The massacre, in an enclave supposed to be under UN protection, was the worst atrocity in Europe since World War Two.

Although Serbia was not legally implicated in the massacre, in 2010 the Serbian National Assembly narrowly passed a resolution that apologized for having failed to prevent the killings. In April 2013, Serbian President Tomislav Nikolić apologised for "the crime" of Srebrenica, but refused to call it genocide. In March 2015 Serbian authorities arrested eight men accused of direct involvement with the killing of some 1,000 Bosniak men and boys at a warehouse in Kravica. It marked the first time that the Serbian government—rather than Bosnian or international courts—had filed criminal charges in connection with the Srebrenica massacre.

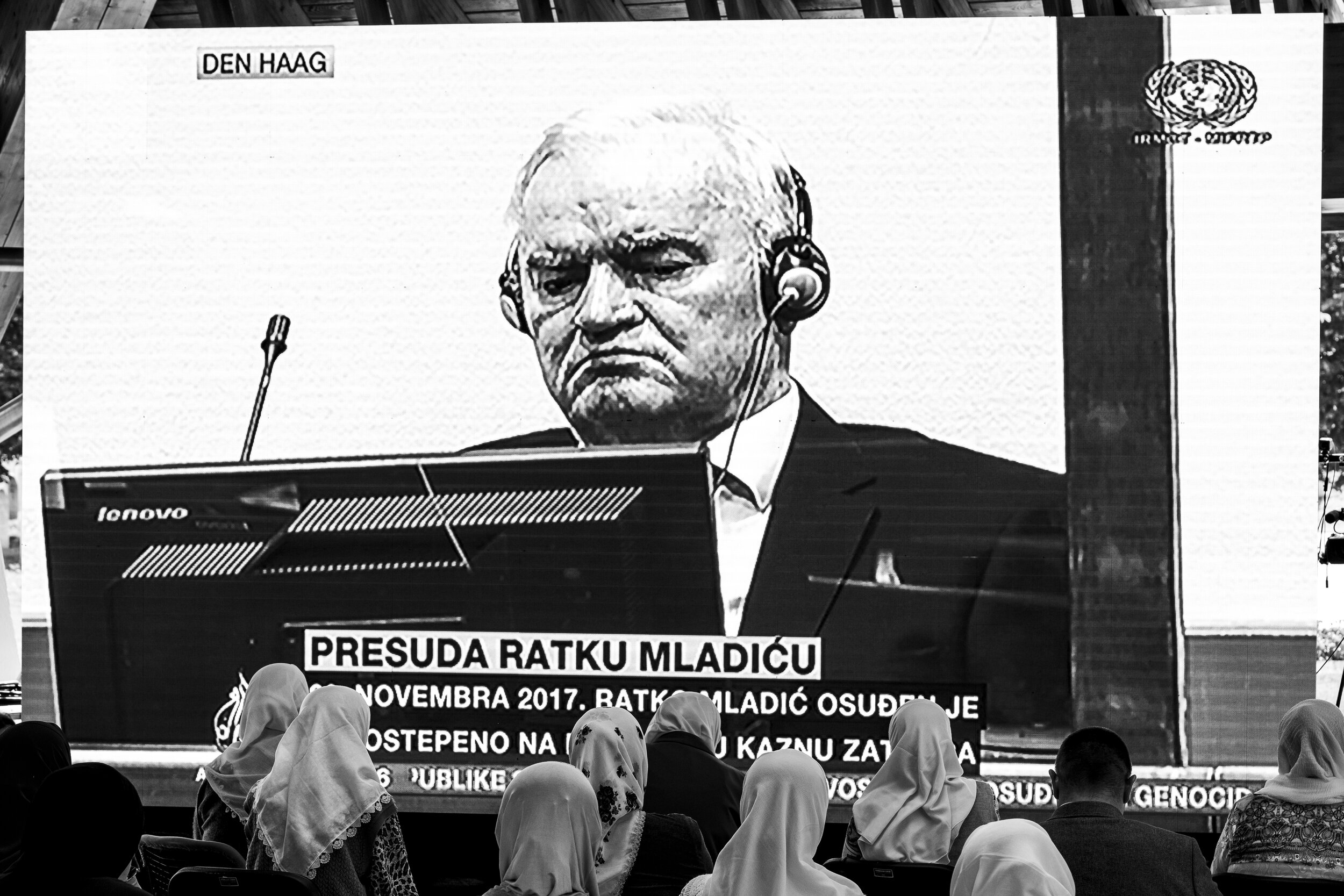

The International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia and courts in the Balkans have sentenced 47 people to more than 700 years in prison, plus four life sentences, for the crimes committed in Srebrenica.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the persistance of genocide denial as well as religious and ethnic intolerance remain enormous obstacles totransitional justice, peace and reconciliation. With rising historical revisionism and ideologies of hatred continuing to endanger marginalized communities our exhibition aims to promote understanding, acknowledgement, tolerance, dialogue, and collective healing.

MIDHAT POTUROVIĆ & N’DEANE HELAJZEN TOGETHER WITH THE US EMBASSY BELGRADE & OCC MLC

CHRISTINE KISIANAN’S STORY // KENYA

12-year-old Christine Kisianan lives in a remote village in Kajiado County, one of the regions in Kenya most affected by the greater Horn of Africa drought, which is in its fourth year. Her family does not have enough food to eat and she sometimes has to stay at home for weeks on end when her parents cannot afford her school fees.

Christine also has type 1 diabetes, a chronic condition whereby the pancreas produces little or no insulin by itself and which mostly affects young people. For those living with diabetes, maintaining a healthy diet and access to affordable treatment, including insulin, is critical. This is a challenge for Christine who often doesn’t know when her next meal will be.

After being diagnosed in mid-2022, Christine has had to adapt quickly to survive and to ensure that she gets her daily shot of insulin. Her parents managed to obtain a fingerstick device which she uses to monitor her blood sugar levels.

“I started injecting myself, monitoring myself. At first, I was very afraid, but I am now used to it,” she says. Despite her adverse circumstances, Christine is hopeful for the future. “I want to go back to school so that once I’m cured, I can help the world,” she says.

Christine has used her experience of living with a chronic condition and in a state of food crisis to look outward. “I want to be a doctor; I want to treat people with diabetes,” she says. “I have become an expert now.”

PHOTOGRAPHS: B. MIARON // TEXT: NATALIE RIDGARD // PRODUCER: N’DEANE HELAJZEN for WHO

TALES OF MIGRATORY BIRDS WITH BROKEN WINGS // SERBIA AND BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA

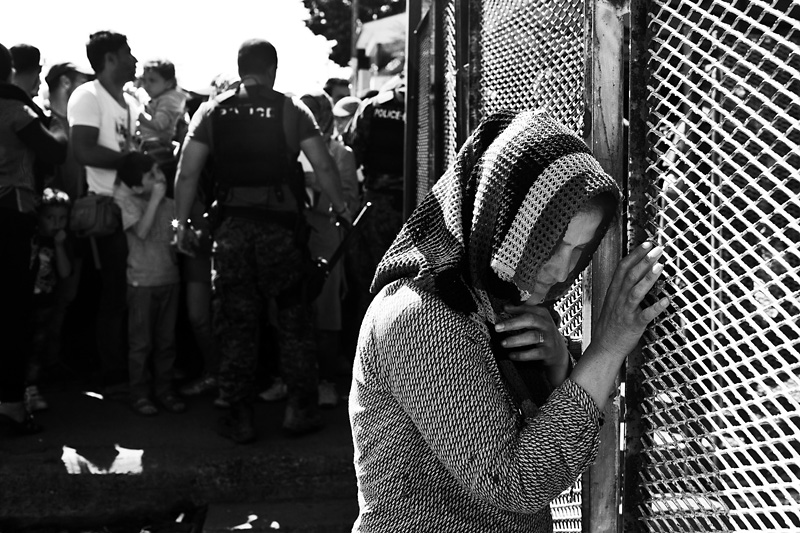

The year 2015 has seen an unprecedented amount of forcibly displaced persons, including those newly forcibly displaced by conflict, violence and human rights violations, and those in situations of protracted displacement, who experience long periods of exile and separation from home. The hundreds of thousands of people crossing through the Balkans from the Middle East and across the Mediterranean from Africa in search of protection have revealed a latent moral crisis that has been brewing for several decades, beginning with the decay of the 1951 Refugee Convention’s ideals.

The agreement reached between the EU and Turkey on the 18th of March 2016 marks the collapse of the principles adopted in 1951. It provides that all asylum seekers, whatever their citizenship, who reach the Greek coast will be forcefully returned to Turkey, a country whose entry into the EU had been refused a few years ago because of its violations of human rights, and whose government has since then become much more authoritarian. Additionally, for every potential Syrian asylum seeker deported from Greece, another one currently housed in a Turkish camp will be relocated in Europe. The resettlements cannot exceed 72,000 people, which factors out to approximately one-fifth of the 363,000 Syrians who have applied for asylum in the EU in 2015. Although already practiced elsewhere—Australia, for instance—this externalization of the asylum procedure is unprecedented in Europe. By preempting the possibility of refugee status being claimed by people from the Middle East fleeing persecution, the joint-action plan counts as the ultimate renunciation of the international right to protection established after World War II. With the increasing militarization of national borders along the so called “Balkan Route”, Serbia and Bosnia have become the main transit countries for people on the move towards Western and Northern Europe. However, what was for a brief timespan an open “Balkan Corridor” has now turned into a “Balkan Prison”, dangerous and without exit for those trapped inside

Today, the systematic fortification of borders is still continuing across South-Eastern Europe, increasingly exacerbating the situation for people on the move. The southern borders of Hungary and Slovenia are completely fenced off now. The same applies to the Turkish-Bulgarian border, part of the Bulgarian-Greek border, the Greek-Macedonian and parts of the Serbian-Bulgarian border. Where borders are not yet physically sealed, they are heavily controlled by police who often use violence as a deterrent. This policy of closed borders does not reduce migration flows, nor does it close the route. Instead, people on the move are forced to seek more and more dangerous paths towards Central Europe.

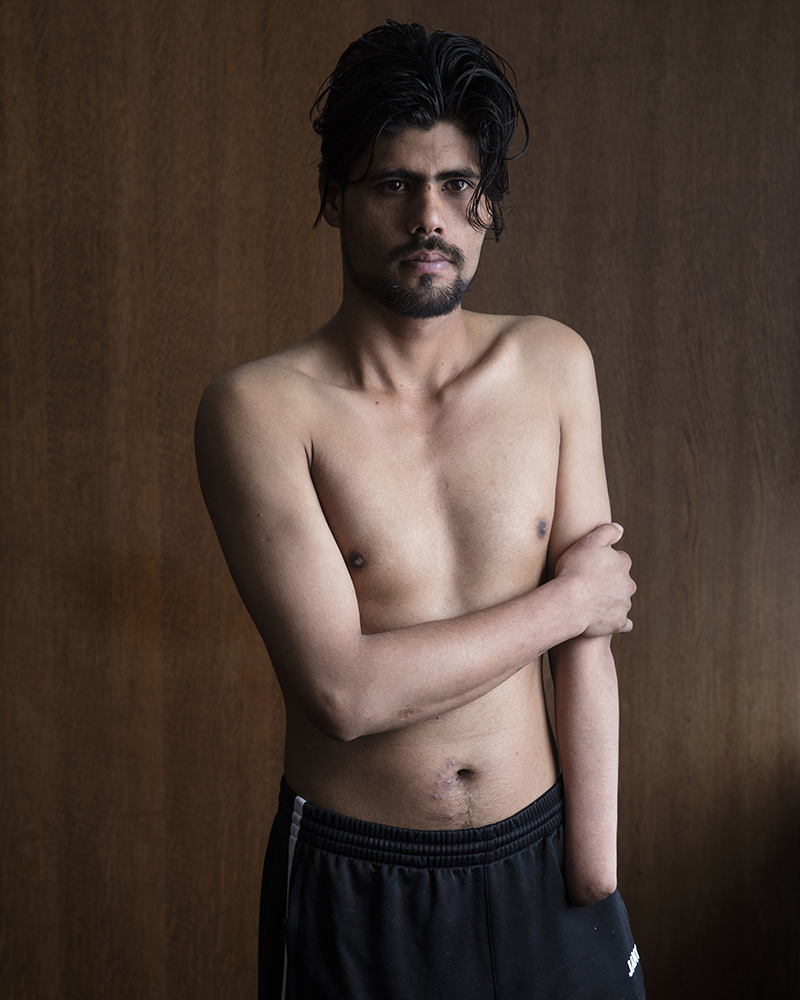

Since there remain very few, if any, legal possibilities to cross the border, many people see themselves forced to go “to the game”. This is the expression commonly used for trying to cross the border irregularly, either alone or with the help of a smuggler, often including long walks in the dark, hiding in lorries or clinging to freight trains. In these “games”, chances for success are dim, and in some cases they end deadly. Those unable to play the game become trapped behind closed borders infinitely waiting. These are their stories.

PHOTOGRAPHS: MARKO RISOVIĆ // TEXT: N’DEANE HELAJZEN

UN-WELCOME // SERBIA

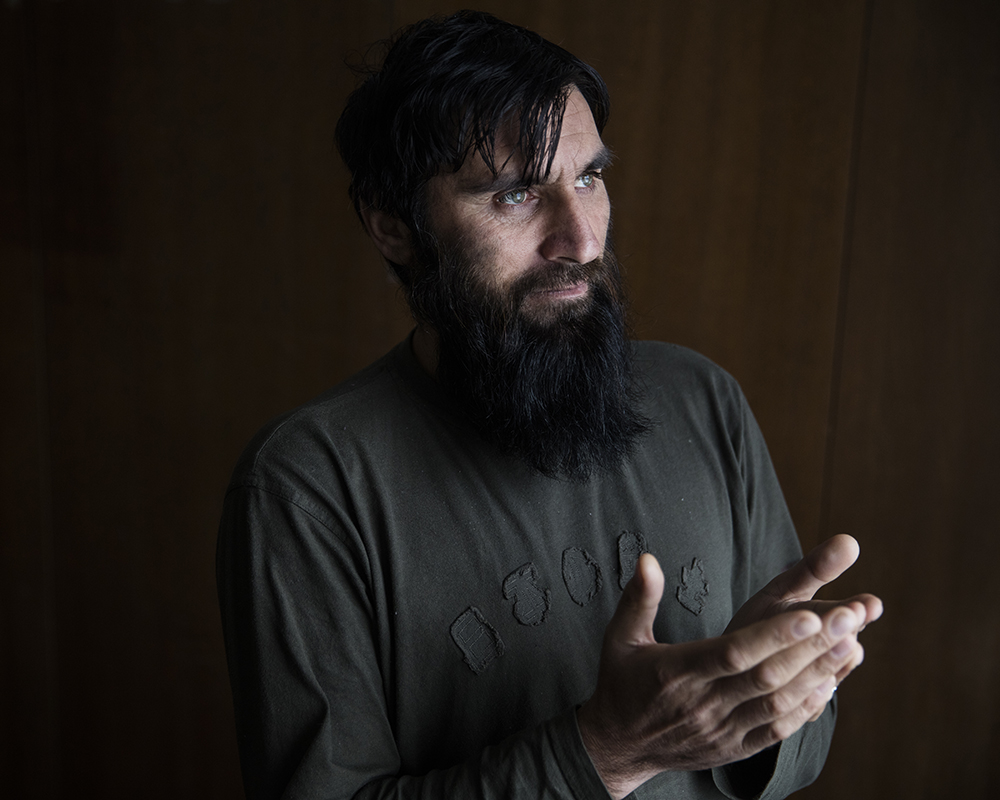

Look in the face of the man behind the barbed wire. Look into his eyes and don’t look away! An entire life fit into that look of hope, anguish, shame and defiance. A man, like any other, of flesh and blood, with his hopes, fears, successes and disappointments, small rituals and big dreams, forced to leave his war-torn home and destroyed country, was sitting in the middle of nowhere, and the only thing that he truly wanted at that time was to have wings.

Rivers of people similar to him streamed the roadless areas of the Balkans, demanding every crevice through which to slip so they could join the main stream, the one that led to the promised safe harbor, refuge from the insanity of the war, and to the peaceful nights without the sounds of bombs and screams of the dying.

During the 2015 refugee crisis caused by the war in Syria and the unfavorable political situation in the Middle East has escalated to enormous proportions. As a result, hundreds of thousands of refugees have started moving along unsafe routes, looking for a better and safer life in Western Europe. The countries of the Balkans have found themselves on this route. Although these countries were not a destination for any refugees, the human tragedy was followed by many heartbreaking scenes, questionable political decisions and tensions in the region. Many demonstrated duplicity, saying that refugees are more than welcome, while closing the borders and aggravating to the maximum their journey.

The truth, written on the faces of these people, can easily be decoded.

PHOTOGRAPHY & TEXT : MARKO RISOVIĆ // WINNER of the BALKAN PHOTO FESTIVAL

THE BEARABLE HEAVINESS OF COEXISTENCE // KOSOVO

This story, although told from one side only – that of Kosovo Serbs, touches many problems representative and important for all the people living in this sensitive area. The purpose of this work is to present the complexity of coexistence of the Serbian minority and Albanian majority in Kosovo today. Like all the other material trying to elaborate this issue, this piece could be a subject to free interpretation, especially in this specific moment. The intention of the author is not to increase or support any nationalistic ideas, but rather the opposite. The basic idea behind the whole body of work is that without tolerance, peace and acceptable coexistence, acquired through learning about the tragic past, neither of the sides involved has the chance for normal future.

As the politicians are again on the loose, rattling arms over the backs of people, and giving their best to keep us all stuck in the Stone Age by causing irreversible differences between us, there is an urge to show the real, everyday problems of those who have been seriously endangered by their hasty, selfish and stupid acts, and who have already been the victims of such politics in the recent past.

Beautiful scenery is something that overwhelms those who come here for the first time. The mountains, woods, rivers and plains illuminated by the sun should illustrate scenery of prosperity and welfare. But this superficial beauty hides dark secrets from the recent past. When one takes a look at beautiful hills around monastery of Visoki Decani, it could be very hard for one to imagine that they were used as a range for a mortar, targeting monasteries after the war finished – in 2000 and 2004. Or areas around cities of Pec, Djakovica and Prizren which hide many graves and tragic stories of prematurely interrupted lives.

In this turmoilous land, Serbs and their neighbors, the Kosovo Albanians, have to find a peaceful coexistence. The Serbs, being the absolute minority today, live in the northern part of Kosovo and on islands of land surrounded by Albanian territories. In everyday life, this means that they have to engage in daily contact with their neighbors. Sometimes this normal and prosaic act of living is not easy to perform at all, which is partially understandable due to all the tragic events from the recent past. Alienation and isolation can almost be touched in the crisp fresh air of the Serbian enclaves among the beautiful hills.

But sometimes, the light of hope sparks from the grayness, as in the smallest local shop in a backstreet of the Serbian village of Velika Hoca, where two friends from the progressive period before the war, Kosovo Albanian Seljami and Serb Stajko, are toasting with home made brandy and cheap beer, remembering together, in clear Serbian language, the time of their lives when ethnicity and religion were not of concern here.

These things will certainly not be an issue in the family of Krsta Simic from Velika Hoca. He married his Albanian wife Pranvera and in this mixed marriage, he achieved his greatest wish – to become a father. Today he says that he is a satisfied man, while his mother proudly holds her two grandsons in her arms. The troubles he sometimes experiences mostly comes from other Serbs living around him and even more from Serbian authorities who hold an ignorant attitude towards his needs and related benefits. Diversity has always been difficult to accept in this region.

For Kosovo, which has a high stake in daily geopolitical games, the future is uncertain. For the Kosovo Serbs, it’s the opaque curtain, and the big question is whether this curtain may need to remain undiscovered forever. Time always finds answers, and until it reshapes the disturbed relations from the past, the neighbors of Kosovo will live in an atmosphere of bearable heaviness of coexistence.

PHOTOGRAPHY & TEXT : MARKO RISOVIĆ // NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC MAGAZINE